Rumble composer Jeremy Richmond and Sweetshop director Trevor Clarence have a conversation on musical collaboration

The creative journey from concept to delivery can be a winding road. With new ideas to explore and opinions to consider, it’s inevitable that projects can take some unexpected turns along the way. Experience is knowing when to run with it and when to steer it back toward the vision. The relationship between true collaborators, with a trust and understanding of each other’s process, can be the difference between delivering magic or delivering compromises. Rumble composer Jeremy Richmond (above right) and Sweetshop director Trevor Clarence (above left) sat down to discuss the composer-director relationship, creative hurdles, and the art of decision making.

Jeremy Richmond: Trevor, we’ve been chatting about how an initial brief changes from the treatment to the final product. How do you deal with that evolution as a director?

Trevor Clarence: It always changes, you just hope that change is in the right direction. You can have a great script but there are many opportunities for it to get messed up along the way. If you’re working with good creative and a good client then there’s the opportunity for discovery. If you’re working with people who are not necessarily aligned with what you’re trying to do, you can end up with a series of compromises.

JR: It comes down to trust, doesn’t it? If you have that relationship with creative and client it makes a huge difference because you actually feel a freedom to explore ideas that perhaps would otherwise get extinguished.

TC: Exactly, it’s a huge thing if the client trusts that you know what you’re doing and that you actually have their best intentions in mind. If you let me follow my plan, it will actually persuade people toward the product and it’ll also be cool.

JR: I think part of that dance is addressing conflicting opinions. You’re often not going to make everyone happy, but decisions should be made on what’s best for the creative and not personal taste. Sometimes you have to sacrifice your own idea or perception of how it should be for the greater good, or trust that someone else has an insight you can’t quite see yet. It’s OK to disagree with a decision and still work to make the outcome of that decision the best it can be.

TC: It can be challenging when people operate out of fear too, because I think you need to embrace your gut instinct making those decisions. If I’m showing spots to a client with some music on it and they enjoy it and they laugh, they should trust that. Often there’s overthinking or over-examining the music. Maybe they’re worried a superior won’t like it, or worried a customer won’t like it. Really we should trust ourselves, because in that moment you are the audience. When people operate out of fear, no good decisions are made in art.

JR: When it comes to approaching a composer, what do you try to incorporate into the brief and in your language?

TC: The most important thing is the intent. If I can articulate what I want the end goal to be, for example that the music’s role is to make it funnier because it’s juxtaposing what’s happening so I need the music to be serious enough to make the silliness funny, then we’ve established a purpose.

JR: Reference tracks are a great shortcut to explain intended emotion or style but, speaking from experience, they can also become a hurdle. How do you use references as a tool and not get attached?

TC: With advertising everything happens so quickly that references are super important. Where it can go wrong is if the reference is some huge well known hit track, then you’re trying to compose something new that still carries all this emotional baggage that you’re just never going to get. I like to go into the edit with a few things to try; some tracks from the composer, some film scores or songs, hopefully none of them too recognisable, and see what works. Once you put it to picture you instantly know ‘that’s it, that works’, then you get composition in as soon as possible so you never develop an attachment to that specific piece of reference music.

JR: On projects we’ve done together, an approach that we’ve found works quite well is writing music before an edit. Even if I write WIPs in a few different directions, working to storyboards helps me get my head around how the music is going to sit, both structurally and emotionally but also the purpose of it within the narrative.

TC: Yeah and for me to just have an idea of the tone of it going into the edit. It’s great to have music before, then we can cut to it, which creates a synergy. We aren’t needing to change the whole tempo of the edit every time we try a new piece of score. Then it’s a case of just saying ‘we need to tweak this or that’, or ‘this direction is working and not the other so let’s continue crafting this one’.

JR: It doesn’t always land perfectly, but to be able to work with a composed track in those early stages definitely helps to craft the musical storyline in parallel with the visuals. If you’re working with the melody and you’re cutting to the tempo, you’re already in that world. You’re not going down one path in the edit and then switching to a composed song that’s completely different later trying to shoehorn it on a locked edit. Then it can be harder to let go of a reference that it was tailored to.

TC: A new piece of music can be invigorating and feel fresh if it works, especially if it’s scoring the right moments. But if it doesn’t work, then everyone keeps loving the old one. It takes a lot of experience to be able to watch something as if you’re watching it for the first time, but you’ve got to keep that perspective so you can move forward.

JR: A huge part of our relationship has been collaborating in the studio, workshopping the track to picture together in the room. Being able to experiment in real time is such an undervalued opportunity. It’s really allowed us to explore concepts quickly or for you to visually see the musical construct and move things around. I feel like we arrive at the final product a lot quicker than by sending things via email and a lot less is lost in translation.

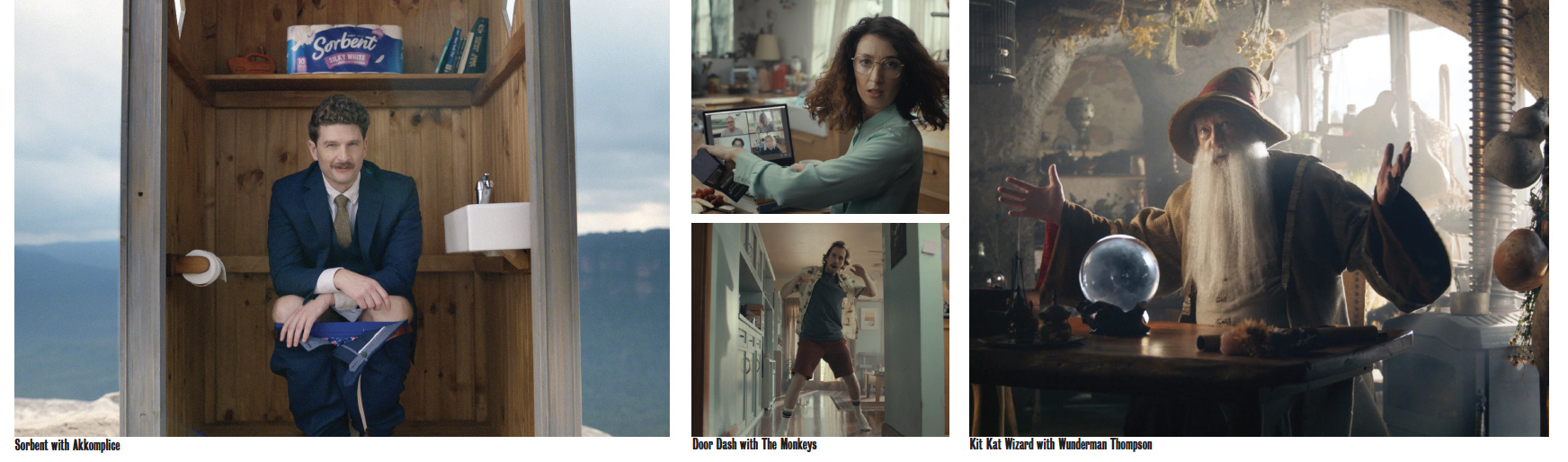

TC: If you just sent me your track and I sent back notes it wouldn’t be the same thing as when I come in. I can say ‘at this moment, I feel like it isn’t that funny. Can we try something?’ And then you’ll cycle through some instruments and play a melody and then it’ll be something that completely surprises us, that makes us laugh. Like when we found the fart trumpet for Sorbent. Together we’ll discover something and I think that’s what makes the process so good. It’s such a shame for people not to take that opportunity if it’s available.

JR: Definitely, and at the end of the day it’s a collaboration. Any kind of creative role in our industry relies on being a good collaborator, being flexible and trusting people at their particular craft. Experimentation is all part of it, I enjoy the ride.

3 Comments

Two of the loveliest. Good read, thanks

Love it! They make it sound so fun.

Great conversation between two clever individuals!