John Newton: People, place and creativity

What do you need for a happy, productive creative department? Former Leo Burnett Sydney creative director John Newton says: Fire the interior designer. Keep the suits in check. And unleash the animals.

I stood staring down a long corridor of cracked grey linoleum flooring, flanked on either side by skimpy plywood office dividers with windows inset overlooking the corridor. There was no decoration, no pot plants. It was tacky and run down.

No way I wanted to work there I thought as I waited to be led inside. And then something absurdly incongruous happened.

From an office at the far end of the corridor, a bloke with long hair, jeans and a white T-shirt appeared on a skateboard. He skated around a corner at the end and out of sight. Hmm. Maybe not such a bad place to work after all.

I’d just come back from three years living out of the country, and had sworn to myself that I would not work in advertising again. I’d had enough. But I’d also had an invitation from the creative director of this agency, Leo Burnett, to come in for a chat. Why not I thought?

I was sucked in. Not just by the money, but by the place, the people and the way the two intersected, as exemplified by the corridor skateboard.

I’m writing this in response to a Ross Gittins piece in The Sydney Morning Herald headlined ‘One of the most exciting discoveries is economics pays a happiness dividend.’

In it, Gittins wrote of the ‘economists’ relatively recent discovery of the economic importance of “place” – where people live and work… at a time when knowledge has become a more critical ingredient, big cities have become incubators, bringing together talented workers to promote experimentation and learning, as well as enabling the transfer of knowledge.’ I was reminded of the happiest, most creative place I have ever worked.

The place – the building – sucked. It was old and tired even by the standard of the daggy ‘70s when I went to work there. The lift from the car park was Jurassic. The only decently fitted out floor was the executive floor where the chairman had his huge office with an adjoining kitchen and boardroom. We’ll get to him later.

The creative floor was a study in neglect and make-do. Furniture salvaged from all over, that grey lino floor, and doors that didn’t close properly from being slammed or fallen against after longish lunches. But none of that mattered.

Because we owned the space. Unlike today, we each had an office where, if we wanted to work or sleep, we could close the door (even if we had to slam it) and get privacy. We were, to borrow an ambiguous phrase from a much later television show, masters of our own domain.

When the suits – account directors, account executives – came onto our floor to brief us they did so knowing they were only there because we let them be there. And if we didn’t want them there, we could tell them to intercourse off.

So that’s the place. How did the people interact with it? That was the secret. And if I had a formula to re-create it and sell it, I’d be very rich. But there was no formula. There was an accidental gathering of individuals who ignited the spark of creativity, First, the creative director.

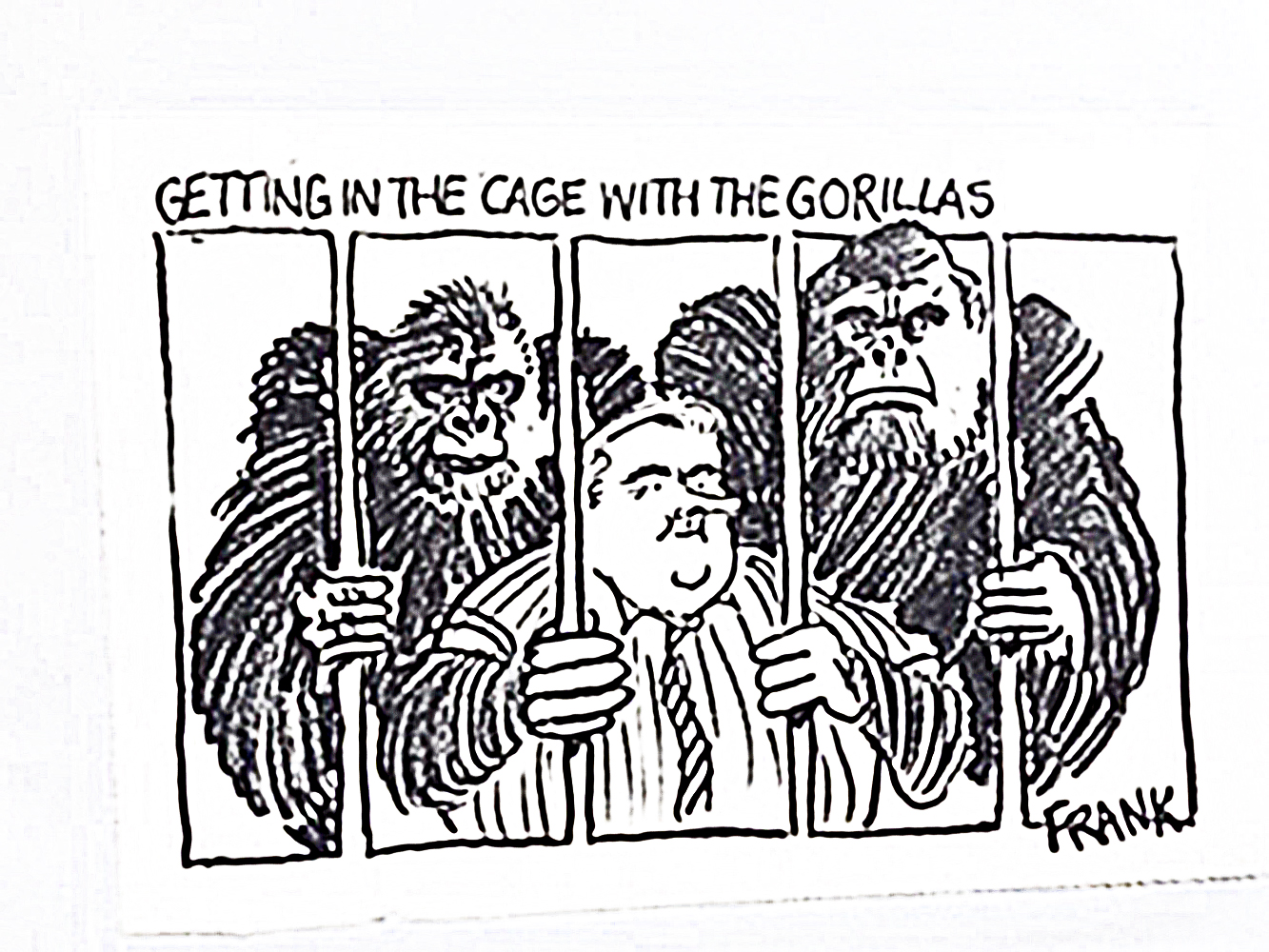

Frank Palmer is a tall Londoner with a constantly bemused expression who ruled his department by caricature, cartoon and laissez-faire. If he had a beef with you, it would appear in cartoon form on your desk. If he perceived some edict from above as ridiculous he would show it for what it was. When it was decreed that all creatives must wear ties, he made ties out of cardboard and we all wore them to every meeting. The edict disappeared. Frank let us get on with our work, allowed us to fight our own battles and only occasionally put a foot wrong.

We creatives, writers and art directors, worked in teams, one writer one art director. We weren’t told when to get in or when to go home. As long as we turned up for meetings, handed in good work on time, that was it. If we wanted to go to lunch until 4pm, fine. But don’t miss a deadline.

(Da Bearded Boyz of Burnett circa late ‘70s early ‘80s – Left to right Rory McCourt, Noel L’Orange, Richard O’Brien, John Newton, Rick Reynolds)

And it worked. Gittins quotes one of our leading economists, Professor Ian Harper, dean of Melbourne Business School, who said that creativity and imagination “are generally stimulated by human interaction, social creatures that we are”. We didn’t need a professor of economics to tell us. But before I finish, a word about our chairman.

The late and entirely graceless Frank Grace was a rotund ball of hard lard one of whose nicknames was Jabba the Hutt (Star Wars fans will get it) and was the author of a book, according to one of our most waggish copywriters, the brilliant and also late Mike Glancy (taken too early by Rothmans) entitled How to Get Ahead Without a Neck.

Grace was cunning, vicious, and shrewd enough to have built the business in partnership with the American giant Leo Burnett and never lose control. He understood little about advertising but knew enough (in the main) to leave the making of the ads to the creatives: as long as the agency made money which in those days was a lot easier for reasons I won’t go into.

As creatives our only contact with him was the occasional boardroom lunch, which exposed us to his legendarily hideous table manners. Only on two occasions do I recall him interfering in a campaign. Both were infuriating. But, in hindsight, probably necessary to save the accounts. On the whole Grace’s presence behind his giant black marble desk was pretty benign, although others may disagree.

(Image: Frank Palmer cartoon of Frank Grace)

There was one snake in this creative garden of Eden: sexism. When I first went to work there, the only women were secretaries and the tea lady, the redoubtable Brenda. Gradually, women wormed their way in. One, who I later married, began work as a secretary, but every brief she typed, she attempted. It worked. She was given a job as a copywriter and later became a creative director. But the presence of women exacerbated the sexism. A story.

The woman referred to above was, while walking the corridor, attacked by two male copywriters, who locked her in a ‘sandwich’, simulating intercourse. She punched them both in the nuts.

Why’d you do that?” one squealed when he had recovered, “we were only bein’ friendly.” It was a different world.

It’s a very long time since I worked in advertising. And I have never since worked in such a convivial, exhilarating, encouraging work environment.

In spite of the awful floor, the crappy offices, the Jurassic goods lift, the total lack of imposed discipline, the graceless chairman – it worked. Gangbusters, as we used to say.

Addendum: While I was writing this, and one day after discussing it with him, one of the Burnetters of the time died. Any of you who remember Noel L’Orange, raise a glass to him. A wonderful human being, a bloody good copywriter. And a better poet.

In his memory, I’ve attached the laws of lunch that we devised, of course, while at lunch.

THE TEN LAWS OF LUNCH

1. Only a fool breaks the one bottle rule (that’s half a bottle each)

2. If you do, don’t go back.

3. But remember, if you play, you must pay. If you don’t go back, you’ll be working back.

4. Lunch is not the point of the day, only the high point. It’s still what you do before or after that matters.

5. Consequently, beware legends in their own lunchtime. Their stories will be short.

6. The long lunch table is a confessional. The same rules apply.

7. The Americans say that breakfast is the most important meal of the day – and eat corn flakes. The French say that lunch is the most important meal of the day – and eat well.

8. Lunch well with a client, and you’ll make a friend.

9. “The table is the only place where the first hour is never dull” Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste.

10. Lunch only with people you like (have meetings with the rest)

John Newton (below) is a writer, journalist, author, teacher and was, for some years, and some years ago, a pretty fair copywriter. His last job in advertising was as a group creative head at Connaghan & May, and before that, at his second stint at Leo Burnett, as creative director. He thoroughly enjoyed his time in advertising where he learnt to write, but probably stayed too long.

2 Comments

Brilliant!

Remember it well. Very accurate memoir.