Why The Word Empire’s Stephen Lacey believes there’s a still a need for long copy in advertising

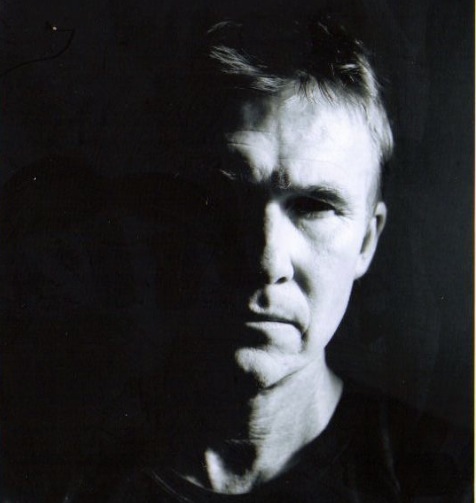

Author, Stephen Lacey has recently launched his Sydney-based long copy agency, The Word Empire.

Author, Stephen Lacey has recently launched his Sydney-based long copy agency, The Word Empire.

“There aren’t many people who can still write long copy,” Lacey says. “In this industry where visual image is everything, it seems to be a dying art form, but I feel we’re about to see a renewed passion for the written word; it’s already happening in innovative ways through the Internet.”

Lacey, who graduated from Sydney University with a Masters in English, is no stranger to long copy; He’s written three novels – The Tin Moon (2002), Sandstone (2005), and Henry Loves Jazz (2009).

Sandstone was shortlisted for the prestigious Commonwealth Writer’s Prize.

Lacey has also worked as a freelance journalist for the Sydney Morning Herald, Daily Telegraph, The Bulletin, and Good Weekend Magazine.

Prior to establishing The Word Empire, Lacey wrote both long and short copy for Stockland, Volvo and Nokia. He has worked with the Love Agency, AdPartners and SapientNitro.

Visit Lacey’s website at: www.stephenlacey.com.au

21 Comments

Here’s some long copy if you like it.

Do long copy ads work?

Let’s ask some of the greatest names in advertising history…

by

George Demmer

In all my years of creating advertising, there is one question that I have been asked more often than any other. One issue that has caused me more problems with clients than any other. One particular advertising and direct marketing approach that creates more concern and disbelief than any other.

So, what is this troublesome question?

“No one is really going to read all that copy, are they?”

Well, since I’m tired of answering this question myself, I propose that we ask some of the all-time greats in the history of advertising and direct marketing what they think about this issue.

Let’s see what they have to say…

David Ogilvy (1911- )

David Ogilvy is probably the most famous advertising personality there is. He not only built the agency he founded, Ogilvy & Mather, into one of the biggest and most successful in the world, he also wrote two popular books on the subject: Confessions of an Advertising Man in 1963 and Ogilvy on Advertising in 1983.

In Confessions, he had the following to say on the subject of long copy:

There is a universal belief in lay circles that people won’t read long copy. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Claude Hopkins once wrote five pages of solid text for Schlitz beer. In a few months, Schlitz moved up from fifth place to first. I once wrote a page of solid text for Good Luck Margarine, with most gratifying results.

Every advertisement should be a complete sales pitch for your product. It is unrealistic to assume that consumers will read a series of advertisements for the same product. You should shoot the works in every advertisement, on the assumption that it is the only chance you will ever have to sell your product to the reader—now or never.

Says Dr. Charles Edwards of the Graduate School of Retailing, at New York University, “the more facts you tell, the more you sell. An advertisement’s chance for success invariably increases as the number of pertinent merchandise facts included in the advertisement increases.”

Ogilvy goes on to discuss some of his personal experiences with long copy ads and shares an anecdote which to this day remains the best explanation of what kind of copy people like to read:

Research shows that readership falls off rapidly up to 50 words of copy, but drops very little between 50 and 500 words. In my first Rolls Royce advertisement I used 719 words—piling one fascinating fact on another. In the last paragraph I wrote, “people who feel diffident about driving a Rolls Royce can buy a Bentley.” Judging from the number of motorists who picked up the word “diffident” and bandied it about, I concluded that the advertisement was thoroughly read. In the next one I used 1,400 words.

We have even been able to get people to read long copy about gasoline. One of our Shell advertisements contained 617 words, and 22% of male readers read more than half of them.

Vic Schwab [you’ll hear more from him later] tells the story of Max Hart (of Hart, Schaffner & Marx) and his advertising manager, George L. Dyer, arguing about long copy. Dyer said, “I’ll bet you $10 I can write a newspaper page of solid type and you’d read every word of it.”

Hart scoffed at the idea. “I don’t have to write a line of it to prove my point,” Dyer replied. “I’ll only tell you the headline: ‘This Page is All About Max Hart’.”

Twenty years later, in Ogilvy on Advertising, he had even more to say on the subject:

All my experience says that for a great many products, long copy sells more than short. [He then goes on to give numerous examples of successful long copy ads.] I could give you countless other examples of long copy which has made the cash register ring, notably for Mercedes cars. Not only in the United States, but all over the world.

I believe, without any research to support me, that advertisements with long copy convey the impression that you have something important to say, whether people read the copy or not.

Direct response advertisers know that short copy doesn’t sell. In split run tests, long copy invariably outsells short copy.

Later, he explains one of the most important differences between the long and short copy styles of advertising:

Advertising people have an unconscious belief that advertisements have to look like advertisements. They have inherited graphic conventions which telegraph to the reader, “This is only an advertisement. Skip it.”

There is no law which says that advertisements have to look like advertisements. If you make them look like editorial pages, you will attract more readers. Roughly six times as many people read the average article as the average advertisement. Very few advertisements are read by more than one reader in twenty. I conclude that editors communicate better than admen.

If you pretend you are an editor, you will get better results. When the magazine insists that you slug your ads with the word advertisement, set it in italic caps, in reverse. Then nobody can read it.

If you abandon the conventional graphics of advertisements and adopt editorial graphics, your campaigns will become islands of good taste in an ocean of vulgarity.

In a later chapter, Ogilvy puts an exclamation point on his argument:

Long copy sells more than short copy, particularly when you are asking the reader to spend a lot of money. Only amateurs use short copy.

John Caples (1900-1990)

John Caples is considered by many in the industry as the ultimate guru of advertising, and his book, Tested Advertising Methods is the closest thing there is to an advertising bible. Originally written in 1938, Caples himself revised the book four times until the late 70’s, and a fifth edition, published in 1997 and edited by Fred Hahn, has been issued posthumously. Here’s what he has to say on our subject:

The short copy ads, set in poster style and containing only a few words of copy or a slogan, are usually used by advertisers who are unable to trace the direct sales results from their advertisements.

Advertisers who can trace the direct sales results from their ads use long copy because it pulls better than short copy. For example, the book club advertisers, the record clubs, and the correspondence school advertisers use ads containing 500 to 1500 words of copy. Also, you will find that real-estate advertisers, patent medicine advertisers, and classified advertisers put as much selling copy into their ads as the space will allow. These people cannot afford to run so-called “reminder copy.” They have to get immediate sales from every ad.

Advertisers who sell their goods and services by means of direct mail letters have found it profitable to use long copy in their advertising. Long copy is such a tested and proven success that the four-page direct mail letter has become a rule rather than an option. Where the instruction used to be “Say whatever you must say, then stop,” it now is, “Say it in four pages and make it worth reading.”

This does not mean that long copy should be used merely for the sake of filling space. Long copy should be used in order to crowd in as many sales arguments as possible.

Here are some additional points Caples makes with regard to length of copy:

Advocates of short copy say, “I don’t think anybody will read all that small print. Let’s cut the copy down to a couple of paragraphs and set it in 18-point type.”

What the advocates of short copy should say, if they want to be accurate, is this: “I don’t think everybody will read all that small print.” This is perfectly true. Everybody will not read it. But the fact is that the very people you are most interested in will read your ad. These are the prospects who will buy your product or service if you tell them sufficient reasons for doing so.

The question arises: Why wouldn’t it pay the short-copy users to make their advertising do the utmost selling job by including more sales talk? Answer: the chances are that it would pay them.

Here is a solution to the problem of long copy versus short copy that should satisfy the champions of both sides of the question. Put a brief selling message into your headline and subheadings. Put your detailed message into small print. In this way, you accomplish two things: (1) You get a brief message across to glancers with your headline and subheads. (2) You give a complete message in small print to the person who is sufficiently interested in your product to read about it.

Later in Tested Advertising Methods Caples goes on to say:

After you have found your most efficient size ad, you should jam your space full of copy, no matter whether it is a one-inch ad or a full-page ad.

Brief, reminder-style copy consisting of a few words or a slogan does not pull inquiries as well as long copy packed with facts and reader benefits about your product or service.

If you want to see efficient use of space, look at mail order catalogs or at the mail-order ads in magazines or in your Sunday newspaper. Some of the strongest-pulling mail-order ads have contained as many as 1200 words of copy set in small print. Don’t be afraid to use long copy or small print. Just be sure that your copy is interesting.

In his 1983 book How to Make Your Advertising Make Money, Caples says:

Ads with lots of facts are effective. And don’t be afraid of long copy. If your ad is interesting, people will read all the copy you can give them. If the ad is dull, short copy won’t save it.

Later in the book, he devotes an entire chapter to long copy ads entitled “How Editorial Style Ads can Bring Increased Sales.” After discussing numerous highly successful examples he says:

If you use the editorial style approach, you will have a powerful factor working in your favor. People buy newspapers and magazines to read editorial material—not ads. Readership studies show that the reading of editorial material is five times as great as the reading of advertising.

Now that we’ve heard from—arguably—the two most famous men in advertising history, let’s ask some of the real pioneers in the field for their views on long copy.

Claude Hopkins (1867-1932)

Claude Hopkins was one of the first to carefully study and test the results of different approaches in advertising. He is believed to have coined the term “scientific advertising” to describe the approach, and his 1923 book by that name remains one of the all-time classics in the field. Not only did his work inspire many of the advertising giants who came after him, but much of his work and his methods are as applicable today as they were in his day.

Consider his thoughts on our question:

Some say, “Be very brief. People will read but little.” Would you say that to a salesman? With the prospect standing before him, would you confine him to any certain number of words? That would be an unthinkable handicap.

So in advertising. The only readers we get are people whom our subject interests. No one reads ads for amusement, long or short. Consider them as prospects, standing before you, seeking for information. Give them enough to get action.

The motto … is, “The more you tell the more you sell.” and it has never failed to prove out so in any test we know.

He spends an entire chapter, called “Tell Your Full Story,” explaining—with numerous examples—the critical importance of presenting a complete sales argument in every advertisement:

When you once get a person’s attention, then is the time to accomplish all you ever hope with him. Bring all your good arguments to bear. Cover every phase of your subject. One fact appeals to some, one to another. Omit any one and a certain percentage will lose the fact which might convince. … So present to the reader, when once you get him, every important claim you have.

The best advertisers do that. They learn their appealing claims by tests—by comparing results from various headlines. Gradually they accumulate a list of claims important enough to use. All those claims appear in every ad thereafter.

This again brings up the question of brevity. The most common expression you hear about advertising is that people will not read much. Yet a vast amount of the best paying advertising shows that people do read much.

Hopkins gives the simple example of trying to convince someone, face-to-face, to change their favourite brand of breakfast food, toothpaste, or soap and adopt a new one. He says:

A man who once does that at a woman’s door won’t argue for brief advertisements. He will never again say, “A sentence will do,” or a name or claim or boast.

Nor will the man who traces his results. Note that brief ads are never keyed. Know that every traced ad tells the complete story though it takes columns to tell.

Maxwell Sackheim (1890-1982)

Max Sackheim was a pioneer in the direct marketing field. In addition to being a famous copywriter (his ad headlined “Do You Make These Mistakes in English?” is one of the most famous and successful ever written and ran profitably for over 40 years), he invented the Book-of-the-Month Club and the negative option approach which have both been adopted by countless companies since then.

Here’s his point of view:

I have never been able to understand why so many advertisers are afraid to use long copy when there’s so much evidence to prove its value; so much in fact that the only reason for using short copy is when there isn’t much to say.

One good test of copy is whether or not it can be cut. If it can be cut, cut it. But when cutting is hard work, you are getting down to bedrock. Tell your story fully and completely. If you can tell it in ten words, fine. But if you need a thousand words, nothing less is fair to the space you pay for.

Victor O. Schwab

Victor Schwab is the author of one of the classic works on advertising, How to Write a Good Advertisement, which was first published in 1962 after he had spent 44 years as an advertising copywriter. An entire chapter of the book is devoted to “How Long Should the Copy Be?” and it contains one of the most complete and well argued explanations of copy length found anywhere.

Here are a few of his thoughts:

Advertisers who are able to check their advertising and sales results carefully have discovered an astonishing relationship between effectiveness and number of words used. They have found that—unless copy is exceptionally fine or exceptionally bad—these ratios of resultfullness to copy length are fairly constant.

The LONGER your copy can hold the interest of the greatest number of readers, the likelier you are to induce MORE of them to act.

Because the sludge of human inertia is so stagnant that too small an amount of copy cannot make that sludge flow into action—unless (and usually even though) the quality of the copy, or the inherent appeal of the product, is tremendously far above average. And it’s a rare copy idea that can be presented with great brevity and still get immediate action.

To sum up: the longer your copy can hold people, the more of them you will sell; and the more interesting your copy is, the longer you will hold them. If you can keep your reader interested, you’ll have a better chance of propelling him to action. If you cannot do that, then too small an amount of copy won’t push him far enough along that road anyway.

Later on, Schwab discusses the reasons why people will read long copy:

What subject interests your reader most? Himself, and his family. So … your copy subject is what your product will do for him, or for his family.

It’s amazing how much copy any person will read, willingly, if it continues to point out these consumer benefits; if you keep making your product win advantages for him.

Continuously interesting presentation of strong consumer-benefit sales angles justifies and rewards the use of longer copy.

A salesman does not say, “How do you do?” speak a few words about his product, then ask you to sign the order. No; he uses enough words to get your emotions and reasoning power flowing toward a sale.

Yet many advertisements virtually say little more than “Hello—Our product is wonderful—Good-by.”

Likewise, it is obvious (but often overlooked) that no reader can be influenced by good sales angles which don’t appear in the advertisement at all.

In other words, if these sales angles aren’t in the copy, then … readers can’t be influenced by them. But if they are there, they at least have the chance of influencing all your readers. And you cannot shorten copy too much, merely for the greater attraction of some people, without running the risk of leaving too little of it to do a good job of selling the others.

Attempting to compromise with this fact, many advertisers try, in effect, to make a deal with the reader. They make dull advertisements short. Yet mere brevity does not make an otherwise dull advertisements interesting—any more than mere length makes an otherwise interesting advertisement dull. Real interest will induce a reader to read longer copy, word by word, whereas the lack of it will not induce him to read even shorter copy.

Schwab hits the nail right on the head when he quotes a remark attributed to Howard G. Sawyer: “Long copy doesn’t scare away readers the way it scares away advertisers.” Now if only advertisers began to realize that…I wouldn’t have a reason to write this article!

Bob Stone

Bob Stone, founder of Stone & Adler, one of the leading Direct Marketing advertising agencies in the world, is the author of Successful Direct Marketing Methods, the bible of the direct marketing field. In the fourth edition of the book, published in 1988, he says:

“Do people read long copy?” The answer is yes! People will read something for as long as it interests them. An uninteresting one-page letter can be too long. A skillfully woven four-pager can hold the reader until the end. Thus, a letter should be long enough to cover the subject adequately and short enough to retain interest. Don’t be afraid of long copy. If you have something to say and can say it well, it will probably do better than short copy. After all, the longer you hold a prospect’s interest, the more sales points you can get across and the more likely you are to win an order.

Walter H. Weintz

Walter Weintz is another direct marketing legend, and was one of the pioneers in magazine and book subscription direct mail when he worked at Reader’s Digest. In his 1987 book The Solid Gold Mail Box, he shares his thoughts on long copy direct marketing letters:

…a question that always comes up, when a mail-order practitioner attempts to explain his [use of long copy], is “wouldn’t a postcard be more effective?”

And usually the observation is added, “personally, I never read all that junk I get in third class mailings. Really now, why do you have to write four-page letters? Wouldn’t a one-page letter do just as well, or even better?”

The answer is, a 4-page letter will generally pull twice as many orders as a one-page letter, provided that the copywriter has something to say, and says it with some skill. This isn’t just an opinion: it has been proved over and over, by tests—where a skeptical client has prepared a one-page letter, in finest prose, and tested it against a long-winded 4-pager.

In fact, Meredith Publishing Company (publishers of Better Homes and Gardens and Modern Living magazines, as well as numerous books and clubs) generally prefers a six-page letter-because their tests have proved that a good 6-pager pulls even better than a 4-pager!

and so on……..

tl; dr

I got bored at,

“…after all my years creating advertising…”

and I stopped reading.

2:44 That’s the point.

No one likes reading long copy. Reading books is different. Long copy in the commercial world is archaic. Just look at how people are communicating – everything is becoming condensed.

People only read what interests them and sometimes that’s the copy in an ad.

9:41 You are so out of touch…….you’re talking extreme niche there.

If people want to read more they go to a thing called www

They don’t seek massive loads of info in an ads. The days are gone and very much dead.

To be clear, I quote from the article:

” ..a renewed passion for the written word; it’s already happening in innovative ways through the Internet.”

Well written long copy, both offline and online, can predispose people to a brand or product long before they start their search engines.

And besides, if a product purchase requires information and consideration, why wouldn’t you show your potential customers you understand that?

Regrettably, 10:01 has a valid point. These days an ad provides an overview, an appetite whetter. If you want more info, you head for the web.

All those people you quote worked in the 60’s. Most of them DIED in the 80’s… you’re on another planet if you think any f those arguments are still valid.

CAT AMONGST THE PIGEONS is alas very much out of date. David Ogilvy died 12 years ago.

Of course long copy doesn’t work if it’s boring (Cat Amongst The Pigeons’ lengthy piece being a perfect – and deliberate – example). Long copy does work if it’s engaging; if it’s entertaining enough to hold the reader’s interest. Sadly, very few writers these days are able to write copy that does that.

3:27

I was taking the piss – no one in their right mind would read all that copy, let alone listen to admen from the 60’s.

Ho ho ho 3:27 and others of your ilk. SUCKED IN!!!

Blah fucking blah fucking blah fucking blah…

Long copy never works. On idiots.

I actually love the use of long copy for the right product, however I have had higher than secondary education and am not Australian so I can deal with more than two paragraphs without a sponsored joke about being pissed at a barbie.

Long copy sadly is dying, I like what the word empire is trying to do but as my mentor taught me “it’s easier to turnaround yourself than get the world to do a U turn”

Images are the future because advertising now has to have the potential to work across a much broader range of nations hence long copy will have non native English speakers tripping over there dictionary if they can even be bothered.

Anyway that’s my rant over. regards

ECD of an awesome agency in Pyrmont, nuff said.

‘there’?

Copywriter at an awesome agency in Pyrmont.

Long copy is dead. long live medium-sized copy.

I landed my first gig in advertising because all the CDs I emailed where happy to have a look at my book for one reason and one reason only. I wrote a long copy email to them, and more than one remarked how refreshing it was to find a copywriter who could actually write.

And that was just a few years ago.

‘Where happy to have a look at my book’, alleged copywriter @ 11:53???

I don’t think so.

There are a few people on this thread claiming to be writers, but can’t write.

There is absolutely no need for long or short copy.

There is a great need for good copy, and it’s as short in supply as it is long in delivery.